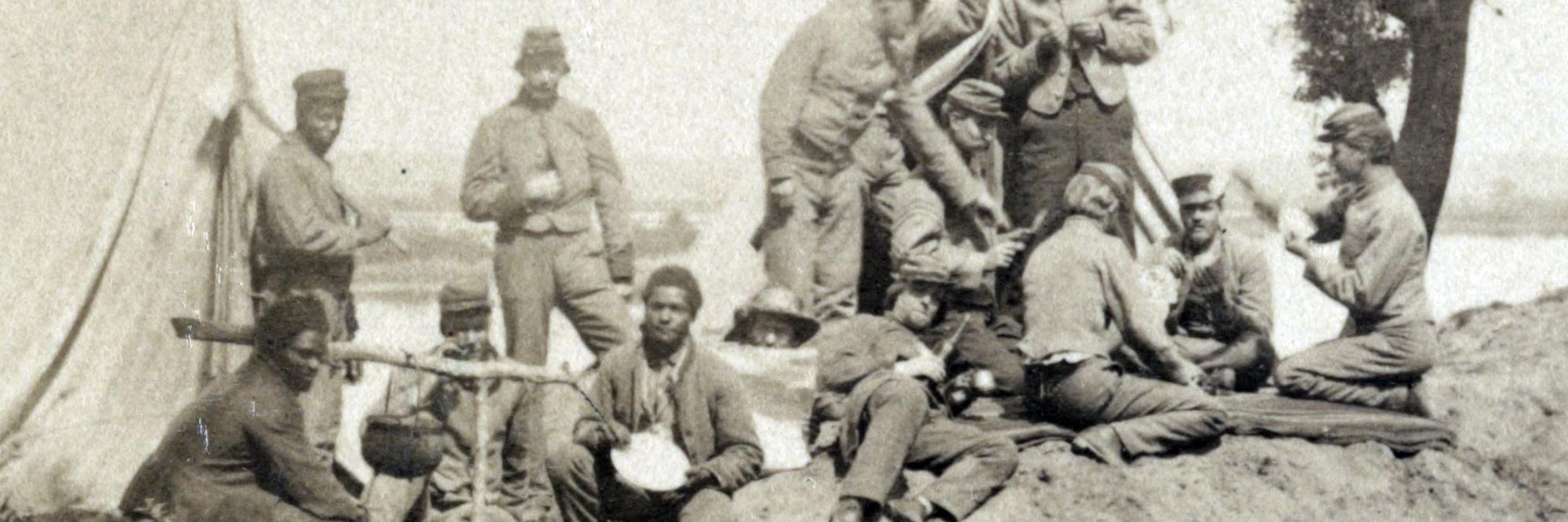

Common Soldiers and Plain Folks

The majority of letter writers from North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama that we include here served privates serving in the Confederate Army. Most were either yeoman farmers who owned the land they farmed or landless tenant farmers or farm laborers. Typical is Thomas Woodham, a Stewart County, Georgia yeoman farmer who owned $700 in real estate and had a personal estate amounting to $425. Jesse Hill of Forsyth County, North Carolina owned a small farm valued at $250 and had a personal estate valued at $300. A. H. Lister of Greenville District, South Carolina owned a farm worth $1500 and a personal estate of $540. Wilburn Thompson of Milton County, Georgia, Jonas Bradshaw of Alexander County, North Carolina and William Riley Jones of Fayette County, Alabama were also farmers by occupation but were among the many letter writers who owned no real estate. All were men of modest means and modest educations; all five were married and had children at home. Of the six, only Jesse Hill survived the war. Thomas Woodham was killed at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. William Riley Jones was killed at the Battle of Chickamauga on September 20, 1863, Jonas Bradshaw was wounded and captured at Gettysburg and died at Point Lookout prison camp in August 1864. Wilburn Thompson was captured at Dalton, Georgia in May 1864 and died at Camp Morton prison camp in August. A. H. Lister was killed at the Petersburg Mine Explosion on July 30, 1864. What they and countless others left behind is a record of what it was like to be a common soldier during the war, the life in camp, sickness and death, the hard marches, and how much they would like to be at home:

[Y]ou writ to me that you wished that I was thar to eat beans withe you but I am A fraid that bean tim will be over with before i Can get to go hom. (Wilburn Thompson to Lottie Thompson, 17 July 1862, Wilburn Thompson Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University)

O that i could bee with you and Budy to see him hug your loving neck and kiss your sweet lips an to see him crall after you. (William Riley Jones to Mary Francis Jones, 5 September 1862, W. R. Jones Papers, Alabama Department of Archives and History)

Carie I wish I had a meal of your cuokin & Some of your guod potatoes it would duo me so much guod to eate some of your cuokin I want to see you & the children the wost kind I hope that day is not far ouf. (Thomas Woodham to Carrie Woodham, 20 October 1862, Thomas Woodham Papers, Hargrett Library Special Collection, University of Georgia)

I wod like to hear from home I hav not heard from you but one time sens I left tell little tomy I hant for got how sweet he is And he dont know how bad I want to se him. (A. H. Lister to Mary Jane Lister, 26 December 1862, Lister Family Papers, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina)

I have all most fur got how home looks I think ever thing would look strange to me I dont expect I would know lodemay [their young daughter] but I think I would know what I would give to see you and your sweet babe but I fear I will meet with meny a obstical be fore I get home. (Jonas Bradshaw to Nancy Bradshaw, 28 March 1863, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University)

[H]ere is a little pretty for little Jane that I fixt when I was Sick be Shore and giv it to her and tel her her pap Sent it to her. (Jesse Hill to Emoline Hill, 25 February 1865, Jesse Hill Letters, State Archives of North Carolina)

There are also letters from wives and mothers and fathers, letters eagerly read by soldiers hungry for news from home. These letters often show how dependant soldiers were on their families to supply “neccessaries,” especially in the way of food, shoes and clothing of all kinds. In July 1861, Letty Long of Alamance County, North Carolina wrote to a son serving in the Confederate Army. Delaney Tucker wrote to her husband while he was serving in the 63rd Georgia Infantry. Rachel Jefcoat of Orangeburg District, South Carolina wrote to her husband serving in the 20th South Carolina Infantry. Wives also wrote about the illnesses of children and other family members, about the challenges of farming without their menfolk, about loneliness. Martha Futch writes to her husband in the 3rd North Carolina Infantry about her apparent pregnancy. Caledonia Medders of Randolph County, Alabama writes to her “grand par” asking permission to make clothing for her baby out of a hand-me-down dress:

I want you to rite to me and tell me if you can get aplenty sutch as stockens and all nesessaryes that yu neade and let me [know] if knot. (Letty Long to John Long, July 31, 1861, Long Family Papers, South Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

[T]he children talk about you every day and all want to see you come home I wish you could come if twas only for a fue days I will try to get you a hat as soon as I can when ever you need cloths or Shoes or any thing that I can make or get let me know and I will send them as soon as I can. (Delaney Tucker to William Tucker, 8 December 1862, W. H. Tucker Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University

I [would] like very mutch if I had a chance to send you somthing that you could eat as you cant get to come home atall eny more I want to see you so bad I cant tell you on paper for it is undescriable I give anny I could but see you come home in good health and as lively as ever I would then feell as I never expect to feell againe while I live. (Rachel Jefcoat to John Jefcoat, 19 June 1862, John J. Jefcoat Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University)

[Y]ou no what me and you was talken about before you left it must be so fore the old foax has not bin to see me yet so i will leaf the subgect. (Martha Futch to John Futch, 22 February 1863, Futch Letters, State Archives of North Carolina)

Deare grand par I seat my Self to drop yo a fue lines I was glad to her yo was well I wold of bin a heap prouder to her of yo a coming home I wold luf to Sea yo. John has left us he wanted to give mee that wosted [= worsted wool] dress I wold not taket without yo leaf [= permission] but I wold luf to hav it to make my baby a cloak. (Caledonia Medders to Solon Fuller, 7 November 1862, Solon Fuller Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University)

The letters tell us what they wore, what they had to eat (or wished they had to eat), how they felt about the war, and most of all, how desperately they missed their families at home. In Poor but Proud, Alabama’s Poor Whites Wayne Flynt writes:

How they lived we can only guess, because moths and rust . . . corrupt the records and relics of the poor, and their homes are as transient as the tenants. They deeded no property, kept no books and made no wills. What they thought or felt we do not know, because they were inarticulate, leaving no literary remains. They are unsung, unknown and forgotten ancestors.1

Although much of what Flynn writes is true, the contents of the Civil War letters tell us a great deal about what they thought and felt. Most of the letter writers may be “unsung, unknown and forgotten” but they were not quite inarticulate, and they did in fact leave a substantial written legacy. According to Bell Irvin Wiley in The Life of Johnny Reb, The Common Soldier of the Confederacy:

It is a significant fact that during the Confederacy a large portion of the middle and lower strata of Southern society became articulate for the first time. Certainly from no other source can so much first-hand information be obtained of the charcter and thought patterns of that underpriviliged part of Southern society often loosely called “poor whites.”2

Civil War historian James McPherson estimates that at least 90 percent of Union soldiers and more than 80 percent of Confederate soldiers were literate, and argues that “Civil War armies were the most literate in history to that time.”3 Of course, literacy in rural America in the 1860s was not necessarily the same as it is today, as anyone who has read many Civil War letters will discover. Educational opportunities were often limited, and if not for the war and the need to communicate with distant family member s, many of the correspondents in these collections might never have written a letter. Julia Camp of Cobb County, Georgia wrote to her younger brother serving in the Confederate Army:

Jo you must excuse mi bad writing for this is the firs letter i ever tryed to Write. (Julia Camp to Joseph Miles, 13 March 1862, Joseph A. Miles Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University)

Elizabeth Chapman of Campbell County, Tennessee also expressed a lack of confidence in her writing abilities in a letter she wrote to her brother, Harvey, who was serving in the Union Army:

[H]arvy you must look over mi bad wrighting and s[p]elling for i cant do nary won you no i dont expect you can read hit you must spell hit and pronanes hit what hit is amost like. (Elizabeth Chapman to W. H. Chapman, 29 May 1864, Chapman Family papers, Tennessee State Library and Archives)

The letter written by Anderson Henderson, a slave in the household of Archibald Henderson of Salisbury, NC, illustrates how poor writing skills were not limited to the lower classes, but also members of the slaveholding aristocracy:

[I]t was near sunset this Evening before I got your Letter and Mr Burr Could hardly Read it. but he said he would look over it again tomorraw and let me know every thing Mistress your Letter are all very hard to Read by any Person exept Mr Burr or Dr John Swann any Person that have been acquainted with you can Read it as for me I Cant make out but very few Words of it and it very often Puzzils Mr Burr. (Anderson Henderson to Mary Henderson, 15 December 1864, John Steel Henderson Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill)

It is ironic that if not for the terrible war that caused so much death and suffering, we would not have such a vast, indeed unprecedented, body of historical and linguistic evidence to draw upon. Because of the war, individuals who might never have written a letter became regular correspondents. Certainly, without the war we would not possess the volume of writing that exists. Two days before Christmas 1864, Joshua Doram of Boyle County, Kentucky, a sergeant serving in the 114th Regiment, U. S. Colored Troops sat down to write a letter to his father:

[I] Am well And Doing well And Hoping thes few Lines will fine you the same when It Com to Han it is with Hart felt Gratitude that i Have Seted my self to rite to you farther [= Father] as i Have never Riten to you Before now farther I want you to Rite soon And Gave me And Ancer from this As soon As you Can. (Joshua Doram to Dennis Doram, 23 December 1864, Doram- Rowe Family Collection, Kentucky Historical Society)

Although the majority of the Southern letter writers were soldiers serving in the Confederate Army and their families, there are also letters by Union soldiers, especially from Kentucky and Tennessee. For example, among the Tennessee letters are four collections written by soldiers serving in the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry (Union), all former prisoners-of-war who perished in the Sultana disaster on April 27, 1865. There are also letters by slaves and former slaves. The North Carolina collections include more than two hundred letters written to North Carolina Governor Zebulon Vance. These letters differ from the other collections in that they are basically requests of various kinds: soldiers and their family members requesting discharges, exemptions, and transfers. There are, however numerous letters by the wives or widdows or mothers of soldiers who were requesting relief and who were undergoing extreme hardship because of an absent husband or son:

[G]ovner vance i set down to rite you a few lines and hope and pray to god that you wil oblige me i ame a pore woman with a pasel of litle children and i wil hav to starv or go neked me and my litle children ef my husban is kepd way from home much longer and i ask you to let him come home. (Lydia Bolton to Governor Z. B. Vance, 5 November 1862, Governors’ Papers, Zebulon B. Vance, State Archives of North Carolina)

[M]y Husban is a man with very little talent I donte want him to go in the army he would do no good ther at home he can do a greate deale I have herd Sed that you was as good a man as every lived or died & I hant a fraid to ask a favar of you I have herd Sed that you was Husban to the Widows Fathers to the olpant [= orphan] & the poor man friend. (Catherine Hunt to Governor Vance, 15 January 1863, Governors’ Papers, Zebulon B. Vance, State Archives of North Carolina)

I am Sixty Four years of age & I have A Sone in the Service & youw Wowld ableg mee verry much by Releaceing him & Let him come home & let him labor for my Supoart for I am a poor Widdow & have No one to labor for mee he is a Shewmaker by trade Dear Sir I have no dout that his officers are Wiling to give him up any moment iff you Will give your consent for his officers Says he is not Able to Bee a Soldier I have grate troble Rasing my childing thare father dide When they War babes & I think it is hard to take my child from mee. (Dista Swindell to Governor Vance, 5 May 1863, Governors’ Papers, Zebulon B. Vance, State Archives of North Carolina)

[I] am a solgers wife my husban dide in the army an left me an six children an thouseande in the same surcumstance i have no meat an no corne nor wheat an what i draw will not by but a little over one bushe of corn a month. (Betty Horner to Governor Vance, 6 August 1863, Governors’ Papers, Zebulon B. Vance, State Archives of North Carolina)

Vance apparently read every letter addressed to him and was able to offer assistance to the families of soldiers, sometimes by interceding on their behalf with incompetent or corrupt local officials. However, he had little power when it came to discharges or exemptions. Dista Swindell’s son, Erasmus, died of erysipelas at Staunton, Virginia about six weeks after she wrote Govenor Vance. The letters illustrate the plight of people on the homefront and the breakdown of civil authority in some parts of the state where citizens were often preyed upon by homeguards as well as bands deserters.

The transcriptions included on the website are limited to those that we have transcribed from images (digital images, photocopies, microfilm scans) of the original documents. We will not be posting transcriptions from published sources or from transcriptions made by others.4

Notes

1 Wayne Flynt, Poor But Proud, Alabama’s Poor Whites. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989: page 35.

2 Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (reprint). Baton Rouge; Louisiana State University Press, 2005: page 192.

3 James M. McPherson, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997: page 11.

4 Our transcriptions of the Boyd family letters form Abbeville District, South Carolina were made in June 2010, before the publication of Boys of Diamond Hill; The Lives and Civil War Letters of the Boyd Family of Abbeville County, South Carolina by J. Keith Jones (McFarland, 2011). The Boyd letters were transcribed from photocopies I made at Duke University in December 2009. Christopher Watford’s transcriptions of some of the North Carolina letters appeared in his two volumes, The Civil War in North Carolina: Soldiers’ and Civilians’ Letters and Diaries, 1861-1865. Vol. 1: The Piedmont (McFarland, January 2003) and Vol. 2: The Mountains (McFarland, July 2003). Watford’s excellent books were invaluable for helping identify potential collections, particularly at Duke University and the North Carolina State Archives. However, we wanted to transcribe entire collections rather than selected letters, and we prefer to make our transcriptions from images of the original documents.

NEXT: Project Directors