Introducing Private Voices

Private Voices is the digital offspring of the Corpus of American Civil War Letters (CACWL) project. Linguists Michael Ellis of Missouri State University and Michael Montgomery of the University of South Carolina began CACWL in 2007 with the aim of seeking and transcribing letters written during the Civil War to gather evidence of regional American English in the 19th century. Today the project has amassed more than ten thousand letters and diaries written during the conflict by common soldiers and their families from all parts of the country.

Private Voices launched in July 2017 with transcriptions of nearly 4,000 letters from four Southern states: North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. In 2018 we added an additional 2,000 letters from four Northern states: Ohio, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Maine. Preparations are now underway to add letters from other Northern and Southern states, as well as additional letters from the eight states we have already introduced.

In addition to the letter transcriptions, we have created two sections dealing specifically with language: “Camp Talk,” which features specialized glossaries of terms we have gleaned from the letters and “Word Maps,” which features dozens of maps that locate some of the most regionally distinctive words and linguistic features found in the letters. (We plan to add dynamic mapping tools in the near future.) We also have a search feature which enables users to search words in context, and users can also check out the website’s “Writers and Collections” section to browse letters, letter writers, and archival collections.

Wrenching Experiences

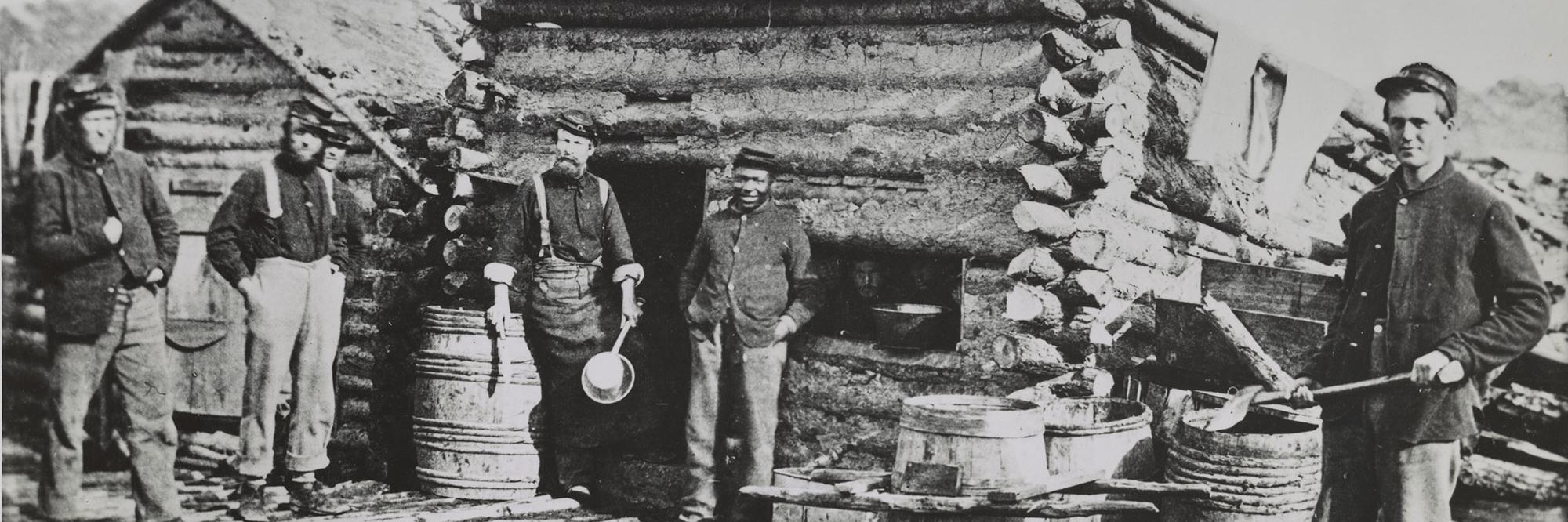

Just as the American Civil War formed the most powerful series of events in the history of the country, it was equally profound and devastating for soldiers and their families. Because it tore at the bonds between so many people, any documents relating to the war have been more likely to be preserved by descendants. Though many were once only private keepsakes and heirlooms, especially in the families of several hundred thousand soldiers who never came home, innumerable letters have more recently found their way into libraries and archives for researchers. CACWL has sought letters of the little-educated privates who were writing not for posterity, but to keep close to family and friends, to dispel their home-sickness, and to follow events they were missing. They were often so desperate for any news from home that, despite their lack of education, they were prompted, in fact were compelled, to write no matter how rudimentary their skills. If not for the painful separation, many would probably have never written a letter in their lives. Letters from privates differ from those of officers in their perspectives on such daily experiences of war as morale, disease, and the privations of poor food, shelter, and clothing, as well as sheer loneliness and other raw emotions. In so doing, they are frequently more powerful than ones by educated counterparts.

Unconventional Writers

The majority of letters collected for CACWL were penned by individuals who often did not feel constrained to follow conventions of punctuation, capitalization, or spelling. Rather than by anything learned in the schoolroom, they tended to write “by ear,” as for example did one soldier who spelled amongst as amunxt–which is such an odd-looking form until it is read aloud. Their inconsistent spellings and lack of punctuation such documents vividly display their writers’ lack of formal schooling and their reliance on spoken language. So does their use of non-standard grammatical forms. This reliance is seen even in common, formulaic phrasings of introductions and closings of letters, which writers have clearly memorized from hearing letters read aloud in camp or from their family circle before the war. Even in these one finds frequent misspellings, typified by “I am well at the present time hoping when those few lines Comes to yore hands they my find you Well and harty.”

A Key to Dialects

Letters like those transcribed by CACWL is an invaluable source of information about American English as it was spoken a hundred and fifty years ago. Thus, the transcriptions included at this website should be of interest to many kinds of historians, including language historians.

The Transcriptions

To ensure accurate transcription we at CACWL have transcribed documents ourselves from photocopies, microfilm, or digital images of original manuscripts whenever possible. So far, over nine thousand letters have been transcribed directly from these formats, mainly by Michael Ellis and his students at Missouri State University. Obtaining images has required considerable travel to archives and libraries. For example, Ellis has made four trips to photograph the extensive collections at the Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University and three trips to photograph letters and diaries at the U. S. Army Military History Institute at Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The preparatory work in accumulating and transcribing documents exhibiting such minimal literacy is painstaking and sometimes frustrating. Besides information about letter writers gathered onsite, we have also used census and military records to find out as much as we can about who these people were and where they lived, as well as basic information about ages, occupations, families, and socio-economic status. The transcriptions are as faithful to the originals as we could make them and have retained all original spellings, punctuation, and capitalization. Editing is minimal except for occasionally supplying a missing word or letter in brackets.

Our Research

Ten years ago when we began CACWL, there were relatively few images of Civil War letters available online. Now, by means of what are generally called “digital initiatives,” a growing number of institutions have made available high-quality images of Civil War letters and diaries. Among those we have used are websites at Auburn University, the Indiana Historical Society, Michigan State University, the University of Iowa, and the University of Vermont. In addition to transcribing letters from some of these online resources, over the last two years we have searched through nearly 1,700 letters, locating examples of important words and grammatical features and extracted citations exhibiting these.

Besides the obvious linguistic significance of the letters, we hope that they will be of significant value to, among others, historians and genealogists. Although our efforts so far have concentrated mainly on collecting and transcribing letters, the CACWL project has resulted in two recent articles in American Speech (the journal of the American Dialect Society), several conference presentations, and the book North Carolina English, 1861-1865, A Guide and Glossary (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2013) edited by project co-director Michael Ellis. Moreover, the two project directors are each preparing book-length studies which draw partly or entirely on linguistic evidence contained in Civil War letters.

The Work of Historians

Since the pioneering work of Bell Irvin Wiley (The Life of Johnny Reb, The Life of Billy Yank) more than sixty years ago, historians have undertaken considerable research using primary sources, including letters and diaries, to help them understand what it was like to be a “common soldier” during the Civil War (see for example Reid Mitchell’s “Not The General But The Soldier” in Writing the Civil War, The Quest to Understand, edited by James M. McPherson and William J. Cooper, Jr., Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998). Works of historians have led us to numerous manuscript collections, and we trust that the letters in CACWL will in turn provide and promote new sources of information for future generations of historians to consult and analyze.

A project like this one relies, more than anything else, on the generosity and cooperation of archives and special collections libraries in the institutions throughout the country that hold manuscript documents. It is they, their staffs, and their supporting administrations who provide copies, lend microfilm, and allow us first–hand access to their collections.

Reading the Letters

The letters we have transcribed retain there original spelling and punctuation. As much as possible, we have kept their original format and have corrected nothing. It is sometimes problematic to make sense of letters with seemingly haphazard spelling and grammar, so we advise reading them aloud, just as recipients did a hundred and fifty years ago, as the best way to make sense of them.

Actually, the spelling is not as haphazard as it may at first seem. There are numerous spellings influenced by pronunciation and the spelling is often somewhat phonetic, but most writers made at least some attempt to follow standard spelling as they knew it. One of the more noticeable features in the letters is the confusion caused by homophones, words that sound alike but have different spellings, such as close/clothes, no/know, right/write, there/their, to/too/two, wood/would, and so on.

In the future we plan to add more information about letter writing that can for the present be found in Ellis (2013).

Editorial Method

If a word or part of a word cannot be read, angle brackets and a question mark ( [?] ) are used to indicate something that is illegible with the approximate number of letters indicated with question marks. Conjectural readings are indicted with the reading followed by a question mark in square brackets ( [word?] ). Missing letters or words are supplied within square brackets ([word]) if the these are likely to confuse the reader. Difficult words, readings, and comments, including identification of individuals mentioned in the letters, are given in notes at the end of a letter. Words that are crossed out in the original but can still be read are indicated with a strike-through (word). Crossed words that can't be read are ignored.