Launch Day for Private Voices

Private Voices has launched! Here is the official press release:

New Online Database Offers Insights Into the Civil War's Common Soldiers

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Center for Virtual History, University of Georgia

September 13, 2017

=====

For all the thousands of books about the American Civil War, the hearts and minds of the conflict's common soldiers have remained elusive. To a large degree this is because historical archives are filled with war-time materials from prosperous and professional families. During the conflict officers had more time to write. Subsequently their descendants have donated their ancestors’ papers to libraries and archives. The result is that we know a lot more about the generals than the privates.

To help overcome this problem, linguists Michael Ellis (Missouri State University) and Michael Montgomery (University of South Carolina), along with historian Stephen Berry (University of Georgia), have created a new archive online (dubbed “Private Voices”) devoted to the letters of Civil War soldiers who wrote “by ear,” meaning they were untrained in spelling, punctuation, or the use of capital letters. Raised in an oral culture, these “transitionally literate” soldiers had little or no formal education and were apt to write ‘amongst’ as ‘amunxt’ because they were unfamiliar with the written form of the word. In the process, such letters sometimes captured not only the thoughts of soldiers but also their speech patterns or even their actual pronunciation—as when one soldier spelled ‘chair’ as ‘cheer.’ Linguists usually work backward from recordings to explore earlier qualities of speech, but Ellis and Montgomery realized that these letters from privates opened up an entirely new avenue that pushed back to a time before sound recordings existed.

The question was whether many such letters still existed. Montgomery came upon a small trove through a historian working on a book on the Civil War in the Smoky Mountains. Ellis took up the hunt in earnest in 2008, driving thousands of miles on trips to dozens of archives, sometimes coming away with a rich harvest of material and sometimes coming up empty. “In the early years,” says Montgomery, “we felt like explorers who had stumbled into a small cave that then kept expanding and continues to expand to this day. Michael rarely knew for sure whether any given archive would turn out to be a large cavern or a tiny one, a dead end. After all, most professional historians we consulted said they had never seen such letters.”

As the number of letters burgeoned from hundreds into thousands, Ellis realized that “what was initially a linguistic investigation began to take on broader historical significance.” The words and faces of common soldiers were coming into sharper focus.

On a research trip to the University of Georgia in 2011, Ellis and Montgomery met Stephen Berry, co-director of UGA’s Center for Virtual History. Berry recognized immediately that the linguists had done a staggering amount of historical detective work. “It was like they had collected all the needles from the haystacks of other archives and brought them together to create a haystack of needles,” Berry says. “They had invented an archive that really could tell us something new about the common Civil War soldier and his family.”

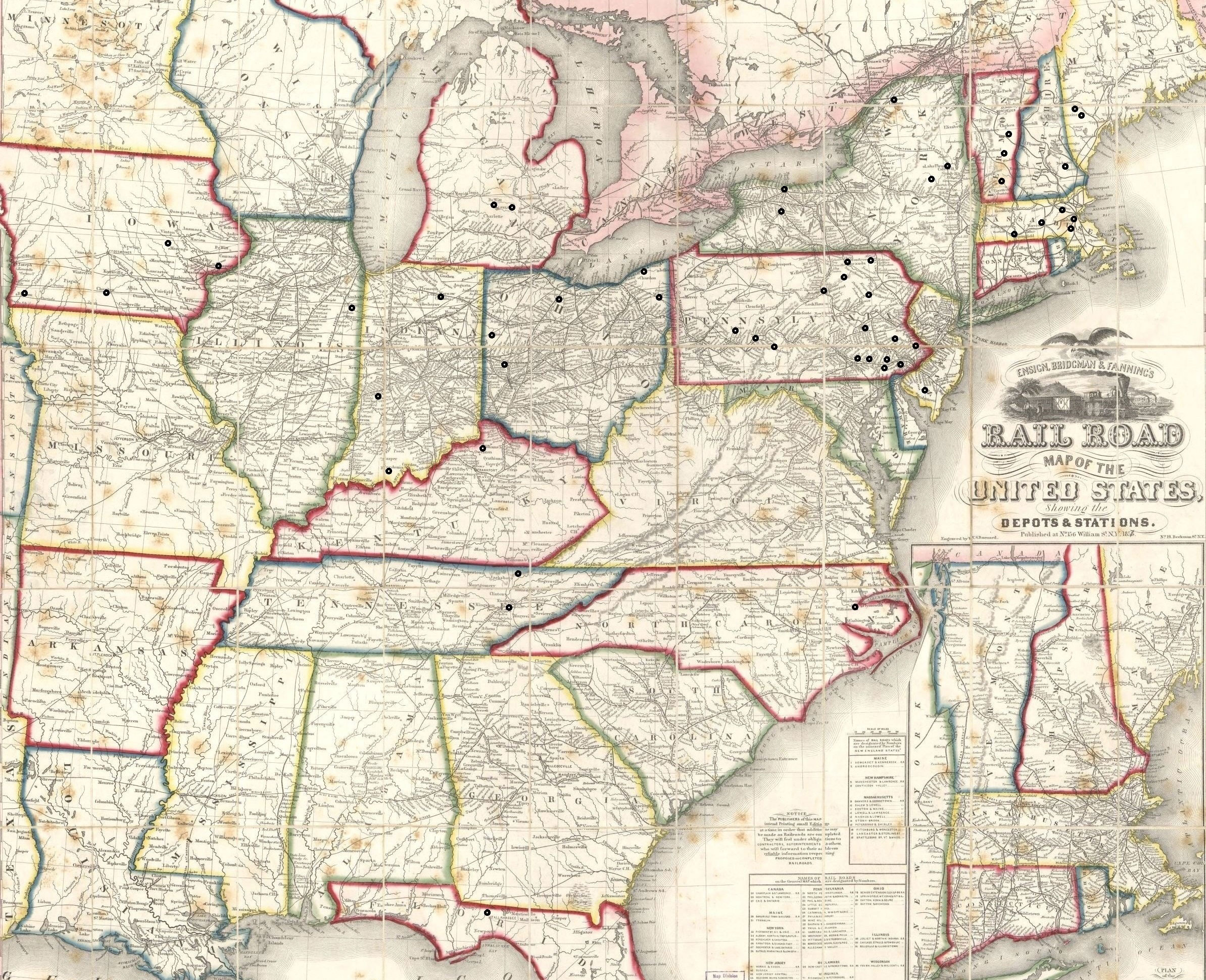

Since then the three researchers have teamed up to create what they call an 'alternative archive' at http://altchive.org/private-voices. The site launches with 4,000 letters from four Southern states: North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. They anticipate adding 6,000 more letters transcribed by Ellis and his students from New England, the Northeast, and the Midwest in the coming year, along with a dynamic mapping feature so users can explore regional variations in word usage and speech patterns. (Ellis has already created some of these maps by hand and made them available on the site.) The project aims at being as representative as possible: North and South, Union and Confederate, black and white, and not just the soldiers, but also those on the homefront.

“Certainly the letters have already provided a wealth of information about American English in the mid-nineteenth century,” notes Ellis. “But for many visitors to the website the letters will be of primary interest for what they tell us about the thoughts and feelings, hopes and fears, of the many letter-writers who might otherwise be forgotten.”